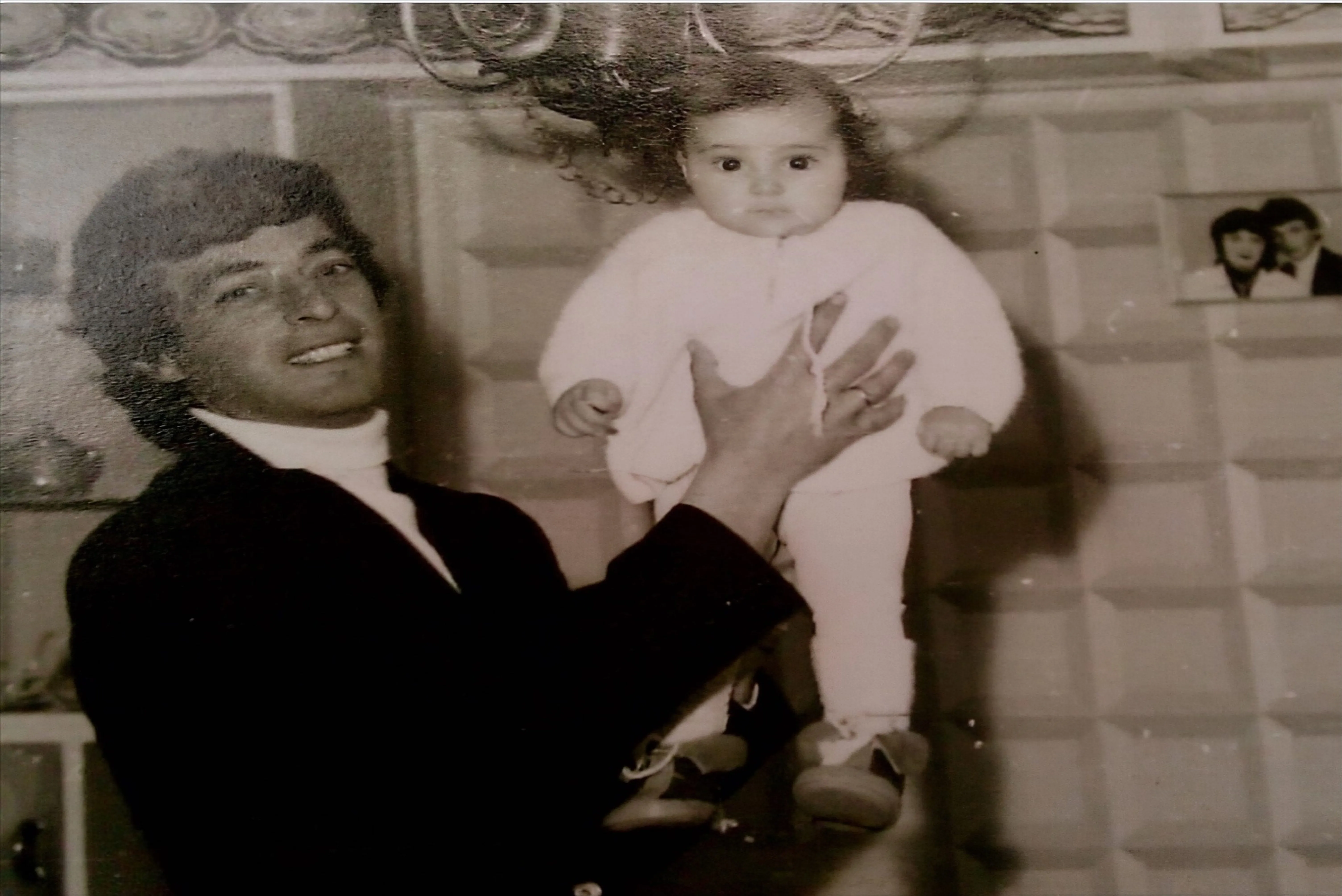

Being My Father’s Daughter — Not a “Daddy’s Girl”

Not a Daddy’s Girl — A Father’s Daughter

I recently came across an article that contrasted being a daddy’s girl with being your father’s daughter.

The distinction stopped me in my tracks. Because while many women speak of being a “daddy’s girl” with warmth or nostalgia, the phrase has always felt foreign to me—almost uncomfortable. Not because my father was unloving, absent, or cruel. But because the idea itself never fit the relational reality I grew up in.

In fact, if I’m honest, the term has always given me a quiet sense of unease.

Why “Daddy’s Girl” Felt Icky to Me

The image of a “daddy’s girl” often carries something soft, indulgent, emotionally doting. A father who rescues. A daughter who is protected from consequence. A dynamic where affection flows freely without expectation, responsibility, or earning.

That was never my experience.

My father was strict. Protective. Authoritative. He had high expectations and a zero-nonsense mentality. Manners mattered. Behavior mattered. Character mattered. Intelligence mattered. Excellence was not optional.

An A was not enough.

It needed to be an A+.

Not because he was cruel—but because he believed that competence was protection.

He didn’t give things “just because.” Everything had to be earned. And as a child, that was confusing. Painful at times. I didn’t yet have the language to understand that love, in our household, was expressed through preparation—not indulgence.

Growing Up Under Authority, Not Adoration

When we immigrated, his protectiveness intensified.

He was a man in a foreign land—without fluency in the culture, the systems, the laws, or the social codes. He didn’t know who to trust. He didn’t know what dangers existed that he couldn’t see coming. And so he did what many fathers do when fear meets responsibility: he tightened control.

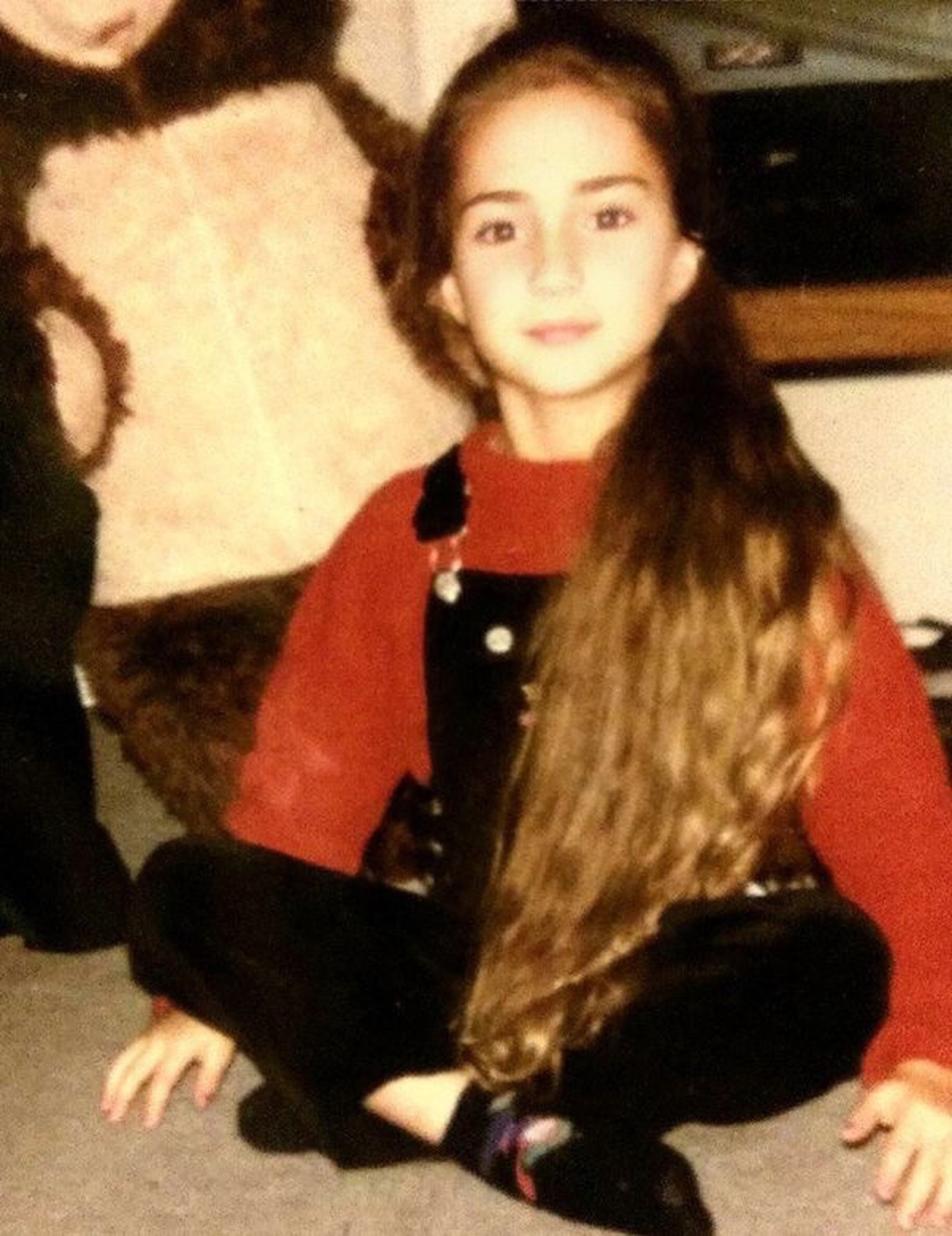

I wasn’t raised to be shielded from reality.

I was raised to survive it.

I was spoken to like an adult from a young age.

Given adult responsibilities early.

Expected to understand consequences, restraint, discipline, and self-command long before my peers.

There was very little room for emotional softness—and even less for entitlement.

So no, I was never a “daddy’s girl.”

I was my father’s daughter.

The Cost — and the Gift — of That Identity

Being my father’s daughter meant learning early that love could be demanding.

That safety sometimes looks like structure.

That approval is not guaranteed.

That worth is proven through effort, not assumed.

That comes with a cost.

It can create hyper-responsibility.

A harsh inner critic.

A sense that rest must be earned.

That love follows performance.

Those imprints don’t disappear just because we grow older or become “successful.”

But there was also a gift embedded in that upbringing—one I couldn’t see until much later.

It taught me endurance.

Discernment.

Self-reliance.

It taught me how to stand up for myself—clearly, firmly, without apology or collapse.

A respect for authority without submission to incompetence.

An intolerance for mediocrity—especially my own.

I learned how to stand in rooms that weren’t designed for me.

How to carry myself with seriousness.

How not to wait to be rescued.

And perhaps most importantly, I learned that adulthood was not something that magically arrived—it was something you trained for.

Reframing the Narrative Without Romanticizing It

This reflection isn’t about glorifying authoritarian parenting.

Nor is it about dismissing the emotional needs of children who grow up too fast.

It’s about telling the truth.

Some of us weren’t raised to be adored.

We were raised to be prepared.

Some of us didn’t experience tenderness first.

We experienced responsibility.

And while that can leave emotional gaps that deserve compassion and repair, it also shaped a kind of groundedness that doesn’t rely on fantasy.

So when I hear the term “daddy’s girl,” I don’t feel envy.

I feel distance.

Because my relationship with my father was never about being cherished for existing.

It was about becoming someone capable of existing in a hard world.

Being My Father’s Daughter, Now

As an adult, I can hold the complexity.

I can honor the ways my nervous system adapted.

I can grieve what wasn’t available.

And I can still respect the intention behind how he raised me.

He responded the best way he knew how. With the tools he had. Under circumstances that demanded strength, not softness.

And I’ve come to understand that being my father’s daughter doesn’t mean I missed out on love.

It means I inherited a particular kind of legacy: One rooted in discipline, responsibility, and survival—which I now get to soften, integrate, and redefine on my own terms.

Not as a “daddy’s girl.”

But as a woman who learned early how to stand on her own feet—and is now learning how to rest without guilt.

An Invitation to Reflect

If this reflection stirred something in you—recognition, resistance, grief, or relief—pause there for a moment. These early relational dynamics don’t disappear; they shape how we work, love, rest, and relate to authority long after childhood.

You don’t have to make sense of it alone. If you’re curious about exploring how your family-of-origin story still lives in your nervous system and relationships, therapy can be a place to do that slowly, honestly, and without judgment.

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)